Beb Moore Campbell was an advocate who worked diligently to shed light on the mental health needs of the Black and other underrepresented communities. Because of her work, Congress formally recognized July as Bebe Moore Campbell National Minority Mental Health Awareness Month to bring awareness to the unique struggles that underrepresented groups face regarding mental illness in the US. Today, BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) is a term used to refer to nonwhite members of society. By including “BI” Black and Indigenous with “POC” people of color, we can honor the unique experiences of Black and Indigenous individuals and their communities.

Alison Swigart, MD, Attending Psychiatrist, Pennsylvania Psychiatric Institute (PPI) has been at PPI for almost 5 years. She works full time in outpatient clinics where she is the psychiatrist for PPI’s CAPSTONE First-Episode Psychosis program and treats individuals with schizophrenia across the lifespan.

She is also an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry And Behavioral Health and the director of the Penn State Community Psychiatry Resident Track for Penn State College of Medicine.

A focus on BIPOC mental health

What drew her to an interest in psychiatry in general, also drew her towards an interest in BIPOC mental health:

“I find it important to get to know individual stories. Everyone’s pathway to where they are in front of you, their journey with mental illness is unique. It can be very rich to understand from an individual level how people get to the point where they’re working with you. I think my experience working in psychiatry has given me a good appreciation for how unique backgrounds and life experiences shape risk for mental illness and its development. It also shapes factors that give people strength and resilience.” Explains Dr. Swigart.

“I work with a population that has a high percentage of BIPOC individuals. When I work with people one on one and get to know them well, I really get to see their value as an individual unique person. I think contrasting that with the prejudice or discrimination or bias that they might experience because of their appearance or the color of their skin in other settings, is what made me very interested and aware of how those factors influence them” describes Dr. Swigart on her interest in BIPOC mental health.

The BIPOC racial groups typically seen at PPI reflect the community’s local population: African Americans and refugees from Bhutan and Nepal.

“One of the things that’s interesting is that people, based on their backgrounds, cultures or maybe their spiritual beliefs, all have different ways of conceptualizing what is causing symptoms of mental illness. There are many times that I will work with people or with families who may have a much different explanation about what’s causing certain symptoms that are bringing them in for treatment. For example, a spiritual explanation would be spirits possessing them.”

“A lot of times people are looking for explanations for what is causing a change in behavior or thinking in themselves or loved ones, and their cultural or ethnic background will influence how they explain, conceptualize or understand it. And so, it’s really important to have the individual or the family explain to you what their conceptualization of it is so that you can try to find areas of common ground in your understanding and be able to partner and work together on finding a solution.”

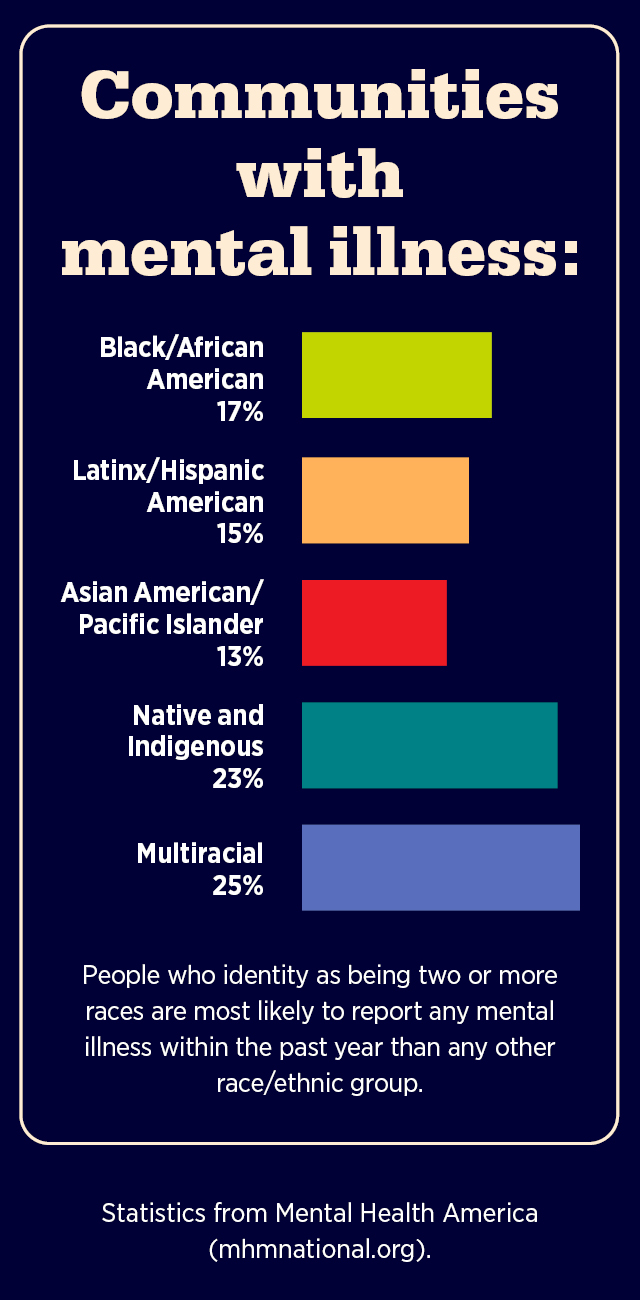

There is data that shows that BIPOC have more difficulties accessing and getting quality care. “BIPOC youth with mental illness or behavioral health problems have been shown to be much more likely to be funneled into the criminal justice system or the juvenile detention system rather than the mental health treatment system. There are demonstrated inequities in terms of how people of color are viewed when they have mental health problems and what kind of interventions they are given.”

Social determinants of health and risk for mental health

Social determinants of health – the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age – influence and shape the development of physical and mental illness. These include factors such as your family, physical environment, neighborhoods, education access, experiences of poverty, experiences of discrimination and opportunity for socioeconomic advancement.

“Unfortunately, because of the historical preference and prejudice towards white people in the United States, many Black, Indigenous and people of color have been put into the position where they face more difficulty with these social determinants of health. That has a downstream effect on both the development of physical health conditions and on mental health conditions.”

Further explaining, Dr. Swigart continues, “For example, when I went through medical school, I was taught that African Americans were more likely to have hypertension or high blood pressure, which has since been debunked as not being a genetic difference or a biological difference. Rather, it is caused by higher chronic levels of stress due to experiences of racial prejudice and discrimination that creates long-term higher levels of stress hormones in the body and thereby elevates blood pressure more often. What’s really interesting is that there are these social influences, these environmental factors that actually work to change our biology. They act on our genes in order to increase or decrease the likelihood of developing certain illnesses, both physical and mental.”

“A lot of these adverse social determinants of health, which can be more common in BIPOC communities, create the conditions for a higher likelihood to develop mental health conditions because of those higher long-term experiences of stress. There’s evidence that race and the experience of race-based discrimination can predict a higher likelihood of development of depression or other mood disorders. It can also predict a higher likelihood of development of PTSD. So, how we how we treat each other as members of society and how we assign different values to different groups based on appearance has a pretty substantial impact on those groups’ health outcomes long term.”

History of misdiagnosis

“In terms of the work I do in psychosis, there are racial disparities in how the diagnosis of psychosis or schizophrenia has been assigned historically. There have been numerous studies that have suggested that Black Americans are two to three more times likely than white Americans to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, and that’s controlling for a lot of other factors which might contribute. There have also been studies that have shown that clinicians are more likely to diagnose schizophrenia rather than a mood disorder or a post-traumatic stress disorder in individuals who are African American compared to their white counterparts.”

“There’s been this tendency historically – probably because of biases that clinicians aren’t always aware of – to over-diagnose or mislabel schizophrenia in Black Americans. Some of this seems to date back to the civil rights era in the 1960s. When you look at the label of schizophrenia, if you look in the early 1900s up to about the 1950s, in state hospitals, schizophrenia was a diagnostic label primarily 1960s given to white women. In the 1960s [during the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S.], it’s been documented that there was a significant shift in the language used to define schizophrenia as being a condition of more violence, anger or aggression. And state hospitals saw a shift in terms of the label of schizophrenia being applied to Black males more commonly than white women. And so historically, there was this shift towards schizophrenia being a label more commonly placed on Black men during that time of civil unrest, while they were fighting for their civil rights in this country.”

Bringing it back to today, Dr. Swigart reveals why this is important for mental health professionals. “We as mental health professionals have to be humble, curious and respectful while trying to understand from the perspectives of the individuals that we treat so that we don’t mislabel something as mental illness when it might just be a cultural or ethnic difference. It’s really important for us to be mindful of our own biases, our own cultural background and how that informs the way that we perceive other people.”

Racial impact on schizophrenia spectrum disorders

Evidence points to Black Americans being less likely to receive effective treatments for schizophrenia, potentially due to their social determinants of health, access issues, sense of mistrust in the healthcare system or the lack of healthcare professionals of color.

“Discrimination or racism in and of itself is a risk factor for developing psychosis. Traumatic experiences are also a risk factor for developing psychosis. So, if you’re a person of color who is treated differently, who maybe suffered police brutality, whose family has been forced to stay in a neighborhood where they haven’t been able to escape poverty, you’re more likely to experience traumatic events and then you may be more likely to develop psychosis later on” notes Dr. Swigart.

“For the refugee population, there are a lot of studies that show that rates of psychosis and schizophrenia are actually higher in people who emigrate to other countries. Probably because of being thrust into a higher stress environment, being thrust into a status of feeling minoritized or marginalized in some way or feeling disconnected from other people around you.”

“When you think about a refugee population, you have to consider traumatic experiences that people have been through. There are just so many factors that make things more stressful, more difficult, more challenging to navigate in a new country, like the language barrier and cultural differences. Often, large geographical or environmental changes in the type of setting they’re living in can all confer a really high level of stress and make people more susceptible to developing mental health conditions. Any experience of trauma is a risk factor for the development of any future mental health condition, not just PTSD, but depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder.”

Stress can manifest physically

Stress can even manifest in physical symptoms. “What I’ve noticed and talking with some other clinicians who treat refugees from New Nepal and Bhutan, there is a greater likelihood of expressing mental distress in the form of physical symptoms. People may come to me as a psychiatrist expressing stomach pain, headaches, body aches or weakness and they’ve been worked up by their primary care doctors and there’s been no medical explanation for it.”

“There’s a book about the effects of trauma that’s called The Body Keeps the Score which talks about how trauma and social environmental factors can change your genes. Trauma can change the expression of our genes; it can change the way our organs function and in some ways it can change our ability to tolerate physical and mental distress. It has a profound impact.”

A better approach

Cultural humility is the concept of approaching another person with curiosity and attempting to understand from their perspective while trying to not make assumptions based on their appearance or ethnic group.

“We need to be careful not to make assumptions about a person’s beliefs or practices based on how they look or what sort of ethnic group they’re from. Because there’s still a lot of variability within an ethnic, cultural or religious group.”

“I have seen and read statistics about Black Americans being often more mistrustful of traditional healthcare systems, and that is rooted in real history of being mistreated by medical professionals. They were mischaracterized, misdiagnosed or having studies done on them without their consent – these are real reasons that Black families might not readily trust and seek out care within the traditional health care system.”

“There are other studies that show that they [Black Americans] may be more likely to seek out solutions from a faith community or from a religious leader, and there’s even some initiatives that I’ve seen presented where mental health professionals are trying to partner with churches or religious leaders in order to collaborate where people can get both the religious and spiritual support they seek, but also the treatment that they might need.”

PPI helps to destigmatize

To help destigmatize BIPC mental health, PPI has an EDI (equity, diversity and inclusion) initiative – a group that gathers regularly to look at policies and procedures, making them more inclusive and helping to identify any training that would be helpful to staff and employees.

“PPI is striving to increase and value diversity among the workforce. They recognize that it makes us stronger both in terms of the care that we can provide for patients and in terms of the support that we can give each other if we have an ethnically and culturally diverse workforce. We also recognize that some people prefer to meet with providers who can speak their native language, who reflect their racial background or have some awareness of their cultural group. There’s a real effort to try to as much as we can recruit providers from diverse backgrounds so that we can reflect the patient population that we serve.”

“Traditionally there are hierarchies and power imbalances within healthcare, but PPI promotes an attitude of respect and valuing the input of all types of employees within PPI. Someone who works as a housekeeper may have a very valuable perspective or input on a patient or can offer a perspective that really is eye opening for the team. Being open and carefully listening to patients’ perspectives and opinions helps us better understand what they’re going through and helps figure out how to find common ground and partner and work towards a shared goal.”

PPI also has specialty clinics, including the Hispanic Clinic , which has Spanish-speaking psychiatry and therapy services, so patients can receive care in their native language.

Dr. Swigart comes to us from the Butler Hospital, Providence, RI. She completed her residency in general psychiatry and served s a chief resident in the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI and received her medical degree from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY.

PPI is available to help. Peruse our website or call 866-746-2496, available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to schedule an appointment.